I’m just checking in today to make sure we’re still covered here by the SBU (or as we would say here in the United States, the FBI). Yep, we are. Beware, miscreants and evil-doers! VLB

Category Archives: What is literature for?

For Admirers of Nature and the Ridiculous in Poetry, “A Sestina by Sesna the Wombat”

Dear Readers,

Here’s a post of a poem I wrote back in 2023, copyrighted on 3/28/2023. Please read and enjoy! (Note that the facts of wombat life are mostly really true, though teatime may be a stretching of the truth!)

Shadowoperator (Victoria Leigh Bennett)

Filed under lifestyle portraits, What is literature for?

Paul Brookes’s Etho-Eco-Poesis in a Simple Statement: Poetic Rhetoric & Influences

Filed under What is literature for?

A Title to Read Before the Lights Go Out in A Winter Storm: “The Meter Reader,” by Victoria Leigh Bennett (copyright 8/1/23)

Filed under What is literature for?

“Seasons in the Sun”–Yet Another Fine Book by Welsh Author Annest Gwilym

Annest Gwilym’s September 2023-published book Seasons in the Sun is a magnificent combination of poetry as natural history, historires of old and new houses which have lives of their own, partly-told love stories, and also a touch of mythology and magic (the death of a mermaid is both that of a mythical person and the fish of the same name). Wales is first and foremost a background, beloved home, and a historical surface for the creative person who would occupy this territory, whether poet or reader.

There are sea captains, sea captains’ daughters, natural adventures along beaches in the surroundings fo sand, tide, and tide pools, old creaking houses which have contained the lives of generations whose lives are also sketched out in brief segments. They have their own stories to tell and contribute to the book, though they do not in general speak directly, with the exception of a sea captain’s daughter. The book, though rejoicing in freedom, is still not without a sonnet and an altered form of a sort of combined villanelle/pantoume, with unique qualities unlike either. There is an elliptical space poem entitled “Insomniac,” which like many of the poems embodies an experience in the form of the poem, and many blank/free verse and also lightly rhymed verse poems (all told, there are thirty-two poems in the book, and three brief notes in the back on them).

The title, of course, comes from the popular 1970’s poet Rod McKuen’s book and song Seasons in the Sun, referred to in one place, and it’s more than worth mentioning that some of the poems are talented polemical, artistic ones on behalf of Wales as a home and landscape. The issues of land-grabbing by greedy developers and rich homeowners is never far from the intense mind of the poet, Annest.

The richness of the poetical/rhetorical surface of the poem in its imagery and tales is kept also simple enough to be enjoyed by any dedicated reader in its commitment to the declarative sentence structure, which seems often to prevail throughout, whle yet the complications of thought on all the issues and the artistry together are brought out by the very beauty of the gifts of the seer-like rhythm.

Annest’s book has only recently been published, as I said, but I would advise poetry-lovers everywhere to celebrate it by a simple purchase (pounds 6.95). Information is available from her for obtaining copies at “X” (formerly Twitter) at @AnnestGwilym. A link also exists and is given on her X account in a post: carreg.gwalch.cymru/seasons-in-the-sun-3008-p.asp. I am thankful to have been a reader of a PDF copy in order to write this review. Thank you, Annest, for sharing your poetical and storytelling gifts.

Shadowoperator (Victoria Leigh Bennett) (P.S.–The cover pages are best seen at 33% before downloading, the brief biography at 50%). This essay is free to read, of course.

Filed under What is literature for?

From the Source to the Sea: An Evocative Journey on the River Liffey with Poet and Musician Billy Mills

Filed under What is literature for?

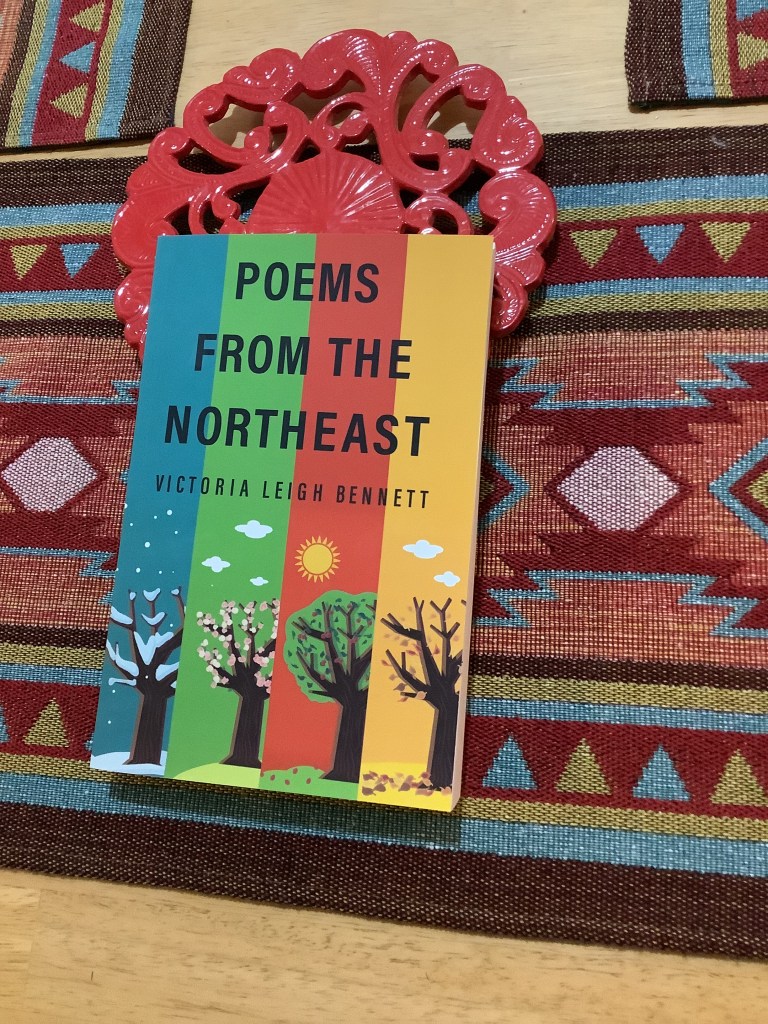

My 2021 book of poetry “Poems from the Northeast” being remaindered in about 1 1/2 weeks–where to get a copy

Dear Readers and Friends,

I have recently received notice from my British publisher, Olympia Publishers (Twitter: @olympiapub) that my 2021 poetry book “Poems from the Northeast” will be remaindered and relevant copies pulped, now in about 10 days. If you are in need of a copy, for 334 pages of all of it, you can obtain it from Amazon platforms (in U.S., $14.95 plus shipping & handling; Book Depository of an earlier notice is now no longer in existence). You can also get it on Kindle, or from the UK publisher directly if you’re quick, at their website (see on Internet through Google). Thank you for your patronage thus far, and happy reading!

Shadowoperator (Victoria Leigh Bennett)

Filed under What is literature for?

Elizabeth M. Castillo’s “Cajoncito”–The Many Poetrys in Which “Love, Loss y Otras Locuras” [Love, Loss and Other Follies] Speak

Cajoncito [A Little Drawer]: Poems on Love, Loss y Otras Locuras [and Other Follies]” is a book of remarkable poetry by Elizabeth M. Castillo, a British-Mauritian poet living in Paris with her family, who has also lived before in Chile, Mauritia, and the DRC. She is widely published in various languages in which she composes, notably English, Spanish of two countries, and French. My introduction to a smattering of her poetry in English two years ago was through Twitter, where I first encountered her work. At long last, when her second book, Not Quite an Ocean is now out and being read, I find the first still holding its own in the warp and woof of my poetic memory (to use an artistic image as much as possible in the manner of the ones I admire in her work). The first book is a tribute as well to her life with numerous other people whom she has loved, and some of whom she has lost.

Her artistic words are ordinary and simple if multitudinous and mightily creatively used words for passion, and feeling. Not only do words in English and Spanish–only the first of which I came to the work knowing more than a smattering of–respond easily and richly to her call, but they say things, visit emotional places one may have felt, but never known how to have put in one’s emotional passport legally.

The territories and lands of the transgressions against love and the grief resulting, as well as grief and longing drawn from other sources crafted for life, are painted here in vivid language colors, sometimes in matched, paired poems in which some words of Spanish in one and English in the other are reversed, sewing the two bright place languages together like the covers of a book of poetry.

There is too much to quote, too many inspirations to follow down the corridors of the heart of this poet’s work: you have to read it for yourself. Before, I have always been a curious but casual peruser of the Spanish version of the English bus and other public announcements on American walls and ceilings, attempting in my primitive way to match the correct pairs of words. For the first time, but I hope not last, I meet the natural aristocracy of someone’s language who has mastered both, and who can vary them back and forth easily at will, making of them in her matched sets of poems a wife and husband completing each other’s sentences, interrupting, interjecting, but always in complete agreement for the reader, who only has to locate the translated portion in the matching poem to learn “for sure” what the “foreign” phase or sentence means. And learning in any way at all is always lovely. And it’s there that the virtue and smugness of “knowing for sure” is also trickily understood in all life ventures to be a form of foolhardiness and loss except in love with life and language, which have in some way to make their declarations of certainty for the time in spite of really not knowing, as the poet more or less outright states she would have it. I find that I almost begin to understand instinctively portions of the Spanish from this gentle and loving example of what used to be called “immersion” learning, as if in the hands of a dedicated and talented tutor or teacher.

Castillo’s major poetic virtue, and she has many, is thus her comprehensive expressiveness and rich texture of images and references to simple enough things about life that become complex again as she puts them in words. One feels almost as if one oneself is becoming gifted enough to understand a new and alien language about life and its doings and “loves, losses, y otras locuras” (as she puts it in her title).

Finally, the greatest reader’s gratitude I have for Elizabeth M. Castillo as the author of the book is that she makes me stretch myself and my own experiences over the framework of her embroidery hoop to be needled and pierced by her lovely work, a set of images and feelings that I never knew I needed so badly before she created them. Please buy this book and read it soon, and then buy Not Quite an Ocean to see what she is doing!

8/5/23, by Victoria Leigh Bennett (shadowoperator)

How a Debut Book of Poetry Dedicated “For Dad” Has Come to Be “For Everyone”–Lawrence Moore’s “Aerial Sweetshop”

Lawrence Moore, who has quite a bit of recent work published in a number of reputable and well-respected places such as Indigo Dreams and Dreich Magazine, and whose Twitter handle is known by many as simply @LawrenceMooreUK, is frankly unassuming as are many poets, and has patiently waited a year exactly for this much-deserved review, while the reviewer dealt with life and its turmoil. I am delighted at last to be able to bring it to my readers. Aerial Sweetshop, though dedicated as a devout tribute “For Dad,” a flyer of planes both full-scale and model, is actually an experience for every poetry reader, whether a rhymed verse addict (where Lawrence’s work shines) or one of those who prefer blank/free verse.

Moore’s verse is one distinguished in substance by melodic, singing rhythms even when not in rhyming verse, and by kind and altruistic notions. Its subjects are those of mysteries and magic, love poems, and always the sky, and looking up and flying (in both of their literal and metaphorical meanings). Its images are drawn from changing landscapes, the landscapes (when not of pure sky) both actual and even more often those of pure imagination, metaphorical landscapes. The loving rhetoric is one of both faith in a single companion’s human goodness, as well as in the charms and chances of harmless mutual mischief. The villains of the piece are responsible for submerged notes of fear of prejudice and unjust punishments, but are overcome by the claims of gentleness and the strength of togetherness. The one exception (and I’m not sure the female figure leading the narrrator in “My Ardent Friend” can actually be called a villain, in any plain sense) is one who leads on to a sort of accepted ritual or initiatory ending, which is not exactly an ending. Ah! A curious mystery to lead us in and on!

There is a temptation with the rhymed poems, because some of us have grown up familiar with or at least exposed to end-rhyme poetry, to jog-trot the wonderful meters and jar the end-rhymes, but in both the other poems, the blank/free verse poems and the rhymed ones, the rhythms change sometimes unexpectedly and stop that bar to good poetry from taking place. In those cases, if you get too caught up in the sound, you risk missing startlingly lovely and human senses in the poems, such as:

1). p. 9–“don’t let the busybodies ask you why/when they mean don’t…”

2). p. 26–“and if you snore all day/and talk while chewing on your food…”

3). p. 39–“The big wide world is interesting;/you are my greatest adventure.”

All in all, this chapbook is so worthwhile that it hardly seems a first effort at publishing poetry. It contains most nobly, generously, and lovingly a poetry that makes its own happiness, with the inclusion often of a pertinent and essential “other,” a rescuer, guide, and companion in the pieces. In conclusion, Moore’s book is a true “aerial sweetshop,” or as an American like me would perhaps put it, a “heavenly candy store,” full of all the sublime things and beings the heart most wants to have.

8/5/2023, Victoria Leigh Bennett (shadowoperator)